How not to predict the future

Why most forecasts are wrong and what to do about it

It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future. - Yogi Berra

History is full of countless tales of heroes consulting oracles, fortune tellers, and other ostensibly future-knowing entities to gain an advantage in war, politics, and love. Our modern-day heroes are business and world leaders and our “oracles” are investment advisors, economists, pundits, and meteorologists, but the story hasn’t changed. Everyone still wants to know what the future holds.

Almost every decision we make concerns the future, so it’s no wonder that we seek certainty in forecasts and predictions. The trouble is, most forecasts turn out to be wrong.

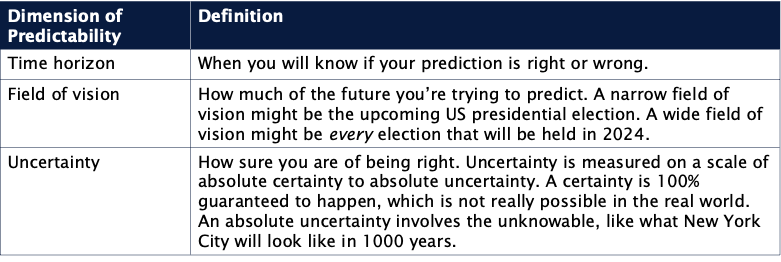

In general, the future’s predictability is a function of how far out you look, how wide your field of vision is, and the level of uncertainty involved in what you’re trying to predict.

Let’s look at a simple example from baseball—an effective if surprising representation of the complexity of our world and the unpredictability of the future—to demonstrate how this works.

At the beginning of the 2023 MLB season, the Texas Rangers had +5000 odds to win the World Series (i.e., you’d win $50 for every $1 you bet), 17th out of 30 teams. By the All-Star Break, the halfway point of the season, the Rangers’ odds had improved to +1000, but that was nothing compared to the odds-on favorite Atlanta Braves at +350.

The Braves ultimately lost in the first round of the playoffs and the Rangers won their first-ever World Series.

Why did the initial baseball predictions turn out wrong? (And yes, I know that betting odds are not predictions, per se, but the bets placed based on those odds are.)

Long-ish time horizon: The forecast dealt with a future 9 months out. This isn’t long by many standards, but it isn’t tomorrow, either. The updated mid-season forecast was still looking out 4-ish months into the future.

Narrow-ish field of vision: Predicting the result of a game or an at-bat is difficult enough, even with advanced statistical models analyzing millions of data points. The entire baseball season involves 30 teams, thousands of players, millions of miles of travel, team and league politics, coaching decisions, and countless other elements. This prediction doesn’t deal with something as complex as the global economy, but it’s a broad, complex scenario nonetheless.

High uncertainty: We can’t know at the beginning of the season which players will have breakout seasons, which will get hurt, how each team will perform over 162+ games, or how the weather could affect a stretch of important games. There is a high level of uncertainty involved in baseball, as in life and business.

Triple whammy! This scenario involves a long time horizon, a not-narrow field of vision, and high uncertainty. That makes for a very difficult prediction.

Baseball is surprisingly complex but much less complex than the global economy or the growth trajectory of a venture-backed startup. There are too many variables at play; too many interconnected systems involved; too much uncertainty to be able to predict what economies or businesses will do next year.

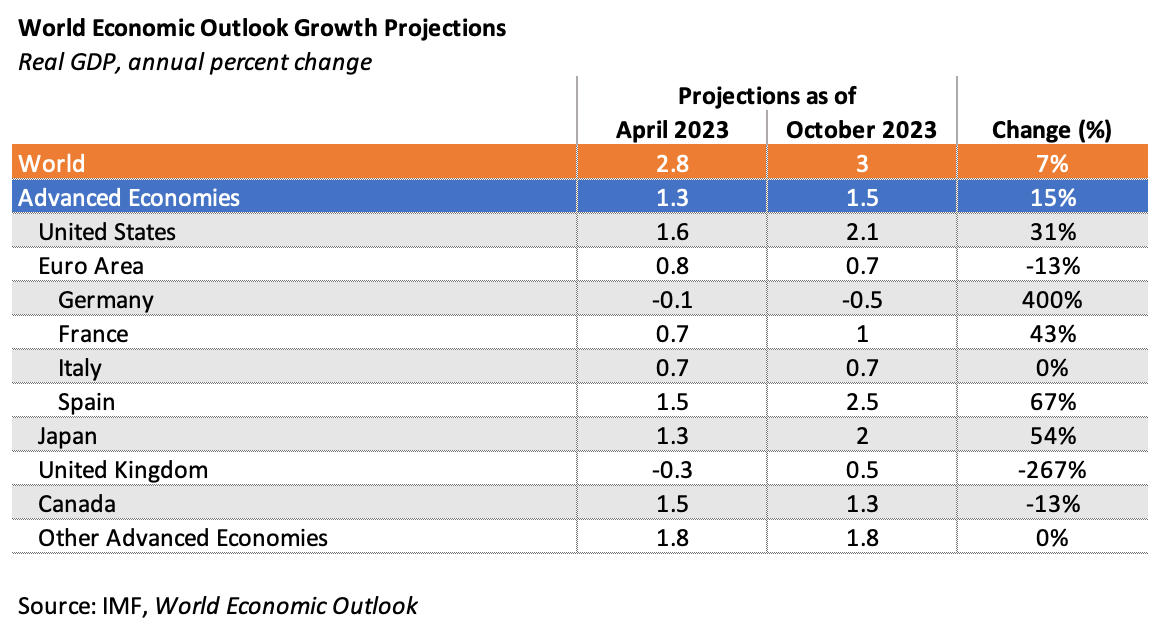

Take this snapshot of the IMF’s mid-year GDP growth forecasts for 2023,1 for example.

In April, the IMF forecasted that Spain’s real GDP would grow by 1.5% in 2023. In October, they increased their forecast by 67%! A lot can change in 6 months. Was the April forecast valuable if it was that wrong? Probably. But making critical decisions based on a prediction that turns out to be wrong can be devastating.

Nearly everything that will happen in the future is unpredictable the farther out you look. That’s why long-range forecasts are always shifting. This is important for businesses to consider as we approach the new year. As you do your strategic planning and read various 2024 outlooks & predictions, you can avoid overreliance on forecasts by doing three things (not exhaustive!):

Don’t take any forecasts as gospel, even your own. Legendary investor Howard Marks has written extensively about forecasts throughout his career.2 He has argued against forecasting for decades, especially in the financial world. For one thing, the people making forecasts are typically investors, not experts in the science of hydrogen energy, geopolitics, or AI adoption. For another, making a wild forecast and being wrong is bad, therefore most forecasts are “consensus” forecasts (like earnings forecasts). There’s not much upside to following a consensus forecast because everyone else probably is, too. The only way to generate outsized returns is to act on a prediction that’s both non-consensus and right (like betting that a company with a low earnings forecast will blow the estimates out of the water).

Directionally correct forecasts can be sufficient for many purposes. However, predicting correctly that Apple stock will go up in a year isn’t much good to you if it only goes up 2% and you could have made more money investing in T-bills. Similarly, projecting 20% customer growth as a startup and using that as justification for massive hiring is a recipe for disaster unless that forecast is right (or wrong in a good way). We’ve seen this playing out with venture-backed SaaS startups around the world over the last few years.

We should be wary of predictions, especially when they deal in absolutes. Undue reliance on any forecast limits our ability to think critically about what we’ve experienced/are experiencing and what that can teach us about the future.

Be prepared to adapt to the future as it materializes. Strategic planning and general future-gazing are worthwhile endeavors for businesses. They help a business organize its strategy, goals, and roadmap, but assumptions used in business planning will nearly always be wrong (sometimes in a good way!). If we learn to adapt as we go by listening to signals in the market, we have a much better chance of succeeding when, not if, conditions change.

Information flows and adaptation are hallmarks of complex systems. For example, desert plants adapt to conserve water when they start to experience the dry summer heat. If they don’t adapt or adapt too late, they often die. Likewise, businesses need to consume and process vast amounts of information to make decisions. They can’t wait until they’re on death’s proverbial door to change their behavior. This requires a commitment to adaptability as an organizational principle and an approach/structure that allows a business to change direction quickly without giving everybody whiplash while staying true to the company’s mission and overall vision.

This is a tough balance to strike, but it is worth it. A company that clings to its forecast/plan/idea of the world when reality diverges from that view is like an old boat captain unwilling to leave his sinking ship. There may be honor in going down with the ship, but not when that proverbial ship is a company that has a duty to its stakeholders to at least try to succeed.

Focus on what you can control but deeply understand what you can’t. Many companies forget the second part of this. You may not be able to control what the weather does, for instance, but you still need to understand it and its potential impact on your business. Even though you can’t control the weather, you can control how you plan for it, react to it, and work with it. You can figure out how to make the unpredictable occurrences in our complex world work in your favor, or at least not work against you, but only if you build your business well (what you can control) and understand how to deal with the systems you interact with (what you can’t control).

The Future is intriguing and always will be. It holds the promise of new and unexpected things. This can be scary, so it’s no surprise that we seek comfort in trying to understand, predict, and control the future. When we accept that we can’t control the future, only shape it, we can focus more on how the complexity of and interactions between systems affect future outcomes. Adapting to system changes, and guiding systems to produce favorable outcomes when possible, is much better than standing flat-footed and hoping The Future that arrives is The Future we want.

Happy holidays!

Cover image from cartoonist Tom Gauld’s Department of Mind-Blowing Theories

Links to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook: April and October 2023

Two of my favorite of Howard Marks’s memos on prediction: The Illusion of Knowledge (2022) and The Value of Predictions, or Where’d All This Rain Come From (1993)